Ana Brotas: Exercise on the fragmented forest. Amazon rainforest, Brazil. Video performance 4:14 min. The concept of forest fragmentation is a terminology that defines the division of large contiguous forest areas into smaller forest fragments. Scientists themselves fragment nature into square areas to more rationally study and explore a particular biome. This methodology inevitably leads to the artificial creation of edges. Forest fragmentation involves meticulously clearing square pieces of forest.

Annegret Müller: o.T. 2018. Berlin. Object, different earths, rescue film. Earth, the soil from which we live, our licentiousness can swallow it, earth I was and earth I become, a gift, the soil from which we live, in trust, with deep bow.

Stephan Groß: Skin of the Earth. 2006, Berlin, Germany, collage, digital print framed, 50 x 60 cm. The collage “Skin of the Earth” shows in the upper part a fragment of an architectural scene the stone wall of a large building, a row of trees and in between a small open space. This apparently merges into the lower half of the image, which shows an anatomical section of human skin. Like the largest human organ, soils are a central condition of our lives. Fertile soil is a finite resource threatened by overexploitation and climate change. Every day we trample it underfoot, build houses and roads on it, and produce our food with its help. Yet “the skin of the earth” is a fragile, complex and fascinating ecosystem that is constantly restructuring itself.

Barbara Karsch-Chaïeb: Arable Land. 2014, Stuttgart, Germany, 30 x 45 cm, photography, Veronese green earth. Ackerland shows a photograph of a field on the Swabian Alb in southern Germany, on it an order with Veronese green earth (from Italy). The basis of life for the cultivation of food is the soil, which is no longer treated with care. (Land) ownership plays just as important a role as competition among farmers. Small farms often go out of business because they can’t or don’t want to compete with large landholdings. Global changes (and EU directives) often shift land ownership and use in ways unfavorable to humans.

Clement Loisel: Rio Morto, 2016, Berlin, Germany, oil and pencil on canvas, 160 x 240 cm. In 2015, the Brazilian district of Bento Rodrigues is covered with the toxic sludge after a mining company dam broke. This painting shows the aftermath of the disaster as an open wound in the ground, combined with ghostly figures from Millet’s famous painting “L’Angelos” praying at the site of the event.

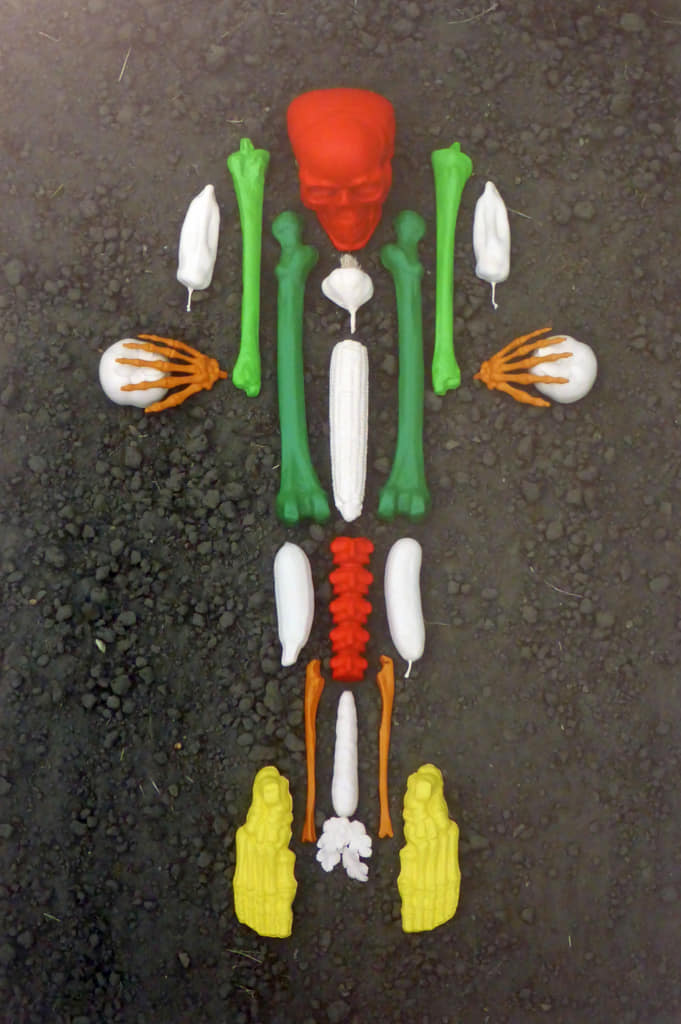

forschungsgruppe kunst: TOTEM / 2018, Rostock, Germany, staged photography. With our work TOTEM we have created, ethnologically speaking, a symbol to represent the mystical kinship connection between flora, fauna and the important resource earth, without which we humans could not exist.

Irene Hoppenberg: The Potato Eaters / 2018, Berlin, Germany, wire mesh, paper, paint. In southern Germany, Switzerland and Austria, the potato is also called Erdapfel. Sometimes remnants of soil still stick to the tuber. It is familiar to us, it is regional, it tastes good, it is healthy and it is the number one indispensable staple food in Germany. The average consumption of potatoes is 55 kg per capita/year. Frederick the Great introduced the potato to Brandenburg to save his peasants from starvation. From 1746, with the potato order, he successfully enforced cultivation by order. At the Academy for Sufficiency in Reckenthin, art and life mix. I work on my subject, a potato sculpture, near potato fields. Cooking and eating together are very communicative. Since a lot of potatoes are grown in Brandenburg, I can ideally harvest potatoes myself from a nearby field and use them to prepare various potato dishes. During the stay at the Academy for Sufficiency, the participants ate together, various potato dishes prepared by me. In reference to the famous painting by Van Gogh, the “potato eaters” and the potato dishes are documented photographically.

Kirsten Wechslberger: Minanimals III ‘The Soil we Live of’, 2018, Reckenthin, Germany, an ephemeral installation of bioplastics and sand, documentary (film), 10 sculptures. Minanimals III is a representation of 10 species of the trillion creatures that live in one cubic meter of earth. It is about bringing into focus life that is invisible (and not perceived) for almost everyone. The sculptures are made of bioplastic and sand, are between 10 and 30 cm tall, and they were each made ten times for the installation. The installation includes 100 individual sculptures – they are built on a piece of land destroyed by humans. There the sculptures will decompose. (and transformed back to earth). Symbolically, in this action, nature takes back its land. The film documents the installation at the place of its presentation. The creatures depicted in this installation are: a bacterium, earthworm, bristle worm, mite, rotifer, rosebug larva, snail, ant lion, water bear and woodlouse.

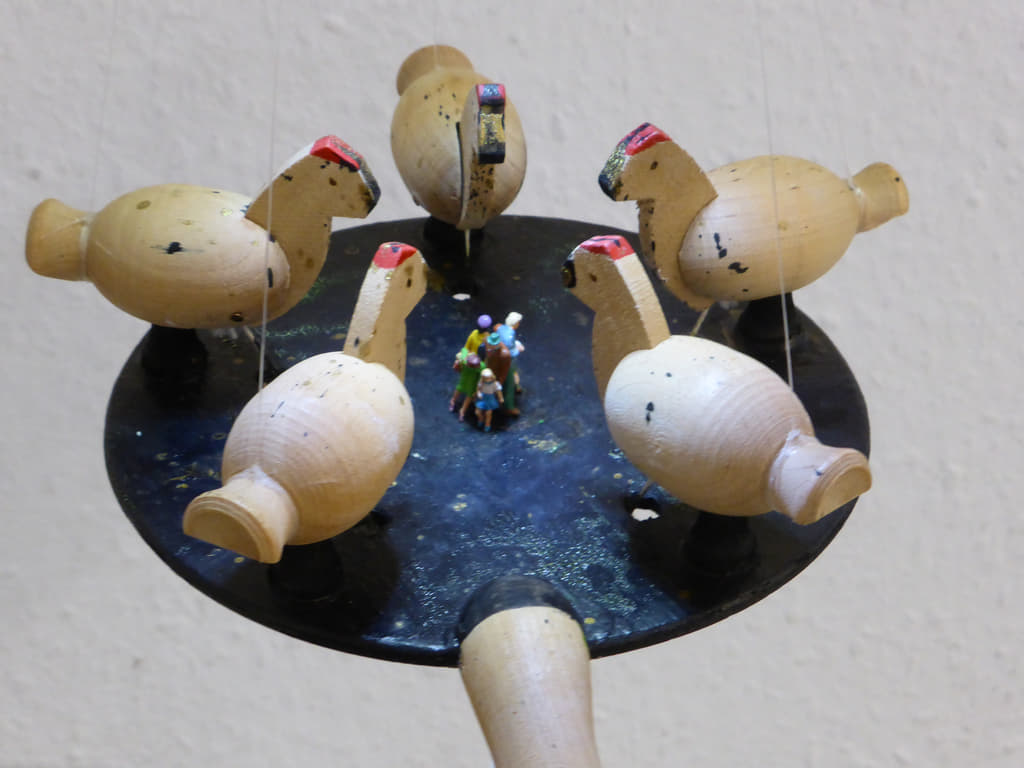

Lioba von den Driesch: bodenschatzen. Berlin, Germany, 2018, 27 cm x 18 cm x 22 cm, modified children’s toy, wood, plastic, string, ink, light. Our daily, comparatively carefree and free life as members of a “western industrial society” builds on the global plundering of the soil above and below ground. The shadow side of our freedom is hopelessness, but for us still in the realm of mind games and private decisions.

Maria Korporal: Breathearth, Berlin, Germany, 2016, interactive installation: Raspberry Pi, monitor, globe, microphone. A video image shows a first view of a desolate landscape, dry and barren. The audience is invited to breathe in a small globe in which a microphone is hidden. With each breath, grass, leaves and flowers appear in the landscape until the whole earth is covered with colors and life. When breathing stops, vegetation disappears after a short time and the landscape turns barren again: the earth needs our breath to stay alive! With each new session, different combinations of vegetation appear – it is always a surprise what flowers are produced by breathing.

Matthias Fritsch: Ecopolis furniture / 2018, Reckenthin, Germany, prototypes made from salvaged, untreated materials. If you want to change something in society, the first place to start is with yourself. How can the city of the future function more sustainably? To this end, Matthias Fritsch develops everyday routines that lead to a more sensible use of finite resources and closed material cycles. The top priority is the floor. Since everyday activities have something ritualistic about them and religions often work with rituals, the daily recommendations for action were summarized under the title “13 Commandments” in reference to the well-known “10 Commandments” of Christians. Fritsch tries to integrate these “commandments” into his everyday life. To this end, he creates practical tools such as a living room humifier or a composting toilet disguised as a piece of seating furniture, with which city dwellers can achieve a more sustainable approach to their waste and close material cycles, even without access to a garden in their own homes. As more and more people live in cities, these tools offer huge potential if applied by the large mass of the population. The furniture is especially suitable for people with little living space or mobile housing.

Oliver Orthuber: Flower Machine, 2018. Berlin, Germany, 45 x 15 x 15 cm, mixed media (earth, ceramic (flower pot), plastic, metal, display). Based on the picture Zwitschermaschine by Paul Klee about the chapter “Zum Ritornell” from the book “Tausend Plateaus” by Gilles Deleuze the idea for the installation Blumenmaschine was born. From the point of view of the role of the ritornello in music, music is considered there, among other things, as a territorial structure: Vogelsang, the singing bird marks its territory in this way. But the ritornello can also have other functions, amorous, professional, social, liturgical or cosmic: it always carries earth with it, sometimes spiritual earth. It has an important relationship with the homeland, with the place of birth. This is exactly the point I would like to pick up on. The earth is the home, the birthplace of humankind and from which we live. Through the flower machine, I want to bring out the aspect of technology that exploitively feeds on the soil and causes man both a curse and a blessing.

Regan Henley: Guided Grief Session 2016. Syracuse, New York, United States, digital video with two channels, 4:06 min. The “Guided Grief Session” aims to analyze and facilitate the unique practice of ritualized and planned grief work. This process of catharsis is organized and pragmatic, with individuals taking time to feel pain and leave room for grief. Although most people think of grief as something that creeps up on us or something we actively push aside and ignore, there is a kind of control in these planned and sustained encounters through our own grief that can be healthy and allow for growth. The video features ASMR (Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response), auditory and visual triggers of the natural land, while the narrated, whispered audio gives the viewer guidance on how to enter into this meditative, highly emotional setting. The objects; the flower, the floor serve as a reminder of the natural process of dying and by extending the natural and healthy process of mourning that should be given space in the daily life we live.

Sabine Naumann-Cleve: Mutterboden, 2018, Ailringen, Germany, 29.5 x 64 x 94 cm, fermented kitchen waste, soil, zinc tub. The top layer of the soil, rich in humus, is topsoil. It is finely crumbly, has a dark color and a pleasant earthy smell. It is healthy and fertile, providing the conditions to grow plants for healthy food. Around the world, however, farmland is drying out, silting up, being overused and poisoned with pesticides. In this regard, fertile soil can be easily produced in any household by fermenting organic kitchen waste. After its fermentation, in another step the mass is mixed with soil and after some time it becomes fertile soil, terra preta. As can be seen, felt and smelled in the zinc tub – completely without artificial fertilizers. This means that waste no longer has to stink and go moldy in the organic waste garbage can, but contributes to a cycle of residual material recycling and reuse.

Tom Albrecht: Landgrabbing. 2018, Berlin, Germany, Collective action, one hour. The soil that visitors bring with them is subjected to a process of appropriation, valorization or devaluation in a joint action and then reused. The problems are sealing, land grabbing, water grabbing, fuel production, legacy, erosion, conventional farming, desertification.

Uwe Molkenthin: Bodenlaib. 2018, Lengerich, Germany, digital photography, digitally processed, art print, 71 x 71 x 1 cm. Seen from a distance, a human being seems to be depicted in a simple form. On closer inspection, it looks like a photograph of a karstified soil. If you look even closer, you can see the surface of a loaf of bread. Our main food.